The mystery never stopped fascinating me. Two Western men depicted together with Indian donors on what seems at first sight an insignificant little pavilion by the wayside. Just after the bypass off Mahabalipuram on the way from Chennai to Pondicherry, at 12°36’37.76″N and 80°10’1.32″E. Who were they? Why and how did they come to be part of what was by all ways and means a Hindu religious building project? Most probably they were 17th century Dutch VOC officials. VOC or Verenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie is the name of the Dutch United East India Company. Judging on the basis of their dress, but also because of the geographical context: Sadras, a coastal VOC trading post and fort, is just 8km away.

As I struggled through the chemo treatments I dug into the old books and sources. Rejoicing in the internet which brought libraries and archives from all over the world to my bedside. And now, as I am slowly rising out of the chemo-ashes, I can share with you the remarkable life-story of two unusual VOC officers.

Eclipse Pavilion

It is now ten years ago that Raja Deekshithar and myself stopped our car for the first time to have a closer look at the little pavilion by the ECR, the East Coast Road, which stretches South along the East Coast of Tamil Nadu. Earlier it had been inaccessible, overgrown with bushes and weeds. In spite of its simple lay-out and structure, just 4 by 6 pillars with a flat roof, it turned out to offer us an unexpected treasure. An unexpected glimpse into an unknown aspect of 17th century religious life. Where Indians and Dutch interacted in an unprecedented way. Actually quite banned for the Dutch.

All across the ceiling of the mandapam there are symbols traditionally connected to astronomy and solar and lunar eclipses: cobras swallowing the sun and moon, the double headed eagle, fish and scorpions, but also a whale, a moray eel, monkeys and tigers. Even an Indian Sphinx and the saint Kannappa together facing a large lotus medallion. On its front porch the donors, Indian dignitaries and their wives, possibly kings and ministers, with folded hands. And together among them two 17th century foreigners wearing heavy coats and hats, their gloves in one hand, a walking stick in the other. One of them showing his high social status by carrying a sword.

Solar eclipse 30th of March 1680

For reasons explained and argued elsewhere, I propose the solar eclipse commemorated by this pavilion is the one which took place on the 30th of March 1680. Eclipses, especially of the sun, are significant spiritual and religious events for Hindu worshippers. It was traditional for kings to perform rituals and make donations on the occasion. The construction project initiated for this 17th century solar eclipse must have been quite a significant one. Besides the pavilion it included the building of a Vinayaka temple and the construction of a large water reservoir, a tirtha or tank. The people involved must have had a high social position, power and very deep pockets.

The Donors

I have no idea who could have been involved on the Indian side. Although I would love to find that out too. On the Dutch side only a handful of people could have had the status, the power and the resources to be part of such an enterprise. First of all, it needs to be clear that involvement in such a heathen, unchristian event in any way would be strictly prohibited to all VOC staff. Although there was plenty of cultural and political mingling, any religious practice outside Christianity was strictly taboo. Not only officially, but probably also socially. Therefore, it took not only money, but also some guts, or some strong personal reason or commitment to involve oneself in such a grand and public Hindu project. And have yourself depicted prominently and on an equal footing with the Indians in the context of this religious structure.

The two VOC officials in charge of Sadras would be logical first candidates. Between 1666 and 1686 Lambert Hemsinck was the chief (opperhoofd) at Sadras, with Antoni de Klerk being his deputy. His rank was that of Junior Merchant, below the highest rank of Senior Merchant. In 1688 Hemsinck was the subject of a corruption inquiry. The superiors of the local officers are also possible candidates. From 1676 till 1679 Jacques Caulier was governor. In 1679-1680 it was Willem Carel Hartsinck who managed that post. And from 1681 to 1686 Jacob Joriszn Pits was the highest authority of the VOC in India. There may be others, possibly also from outside the VOC, but for reasons that will become evident below I focus straight away on Willem Carel Hartsinck as primary candidate for being involved in this astronomical religious construction project.

Carel Hartsinck

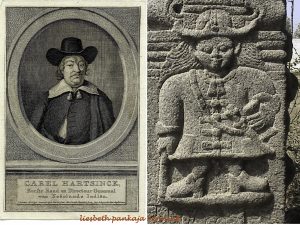

What clenches the argument for me is not a ton load of refined historical arguments based on digging in archives. Although I do hope to undertake the same in future for further eliciting this very interesting family’s life history as revealed by the reliefs of the Indian pavilion. The key which unlocks the door to solving this riddle is a portrait.

Willem Carel Hartsinck was the topmost authority of the VOC in India in 1679 and 1680. Willem Carel entered the service of the VOC in Surat, Gujarat, in 1651, when he was just 13 years old. He worked in administration as well as in the military, making steady progress in his career. By 1663, aged just 25, he had become chief director at Golconda. Today it is the city of Hyderabad, in the 17th century it was the capitol of the Sultanate of Golconda. When in 1679 the governor Jacques Caulier died, Willem Carel, being his deputy, became governor, the highest authority of the VOC in all India.

This is a rather typical VOC career. Especially as Willem Carel’s father, Carel Hartsinck (1611-1667), was a very experienced and highly placed VOC officer. He was the Governor General for the whole of the VOC at Batavia at the height of his career. I have found two portraits depicting Carel Hartsinck. One is a miniature giving the date of his death. The other one was done in the latter half of the 18th century by Jacobus Houbraken “after the original, kept with the Honorable Squire Cornelis Hartsinck Jansz., former alderman of the City of Amsterdam” (“na ‘t origin, berustende bij de Wel Ed. Gestr. Heer Cornelis Hartsinck Jansz. Oud Schepen der Stad Amsterdam”).

A portrait as key

Now when we place the portrait of Carel Hartsinck side by side with the relief of the eclipse mandapam near Sadras we can observe a general likeness between the look of the one and the other. Besides the general look, several details are similar: the wide brimmed hat, the coat with its typically Dutch closing (called houtje-touwtje jas), the tassels at the collar. Even the features of the face. Could the person depicted on the pavilion with a wide hat and sword be Carel Hartsinck, the father of Willem Carel Hartsinck?

Understanding a painting or drawing as the source of the relief would also explain one of its peculiarities: it looks like a children’s drawing. This particular depiction is strange and very dissimilar from the high quality and natural look of the other portrait reliefs found on the front porch of the pavilion. Carel Hartsinck died in 1667 in Batavia. So in 1679-80 the artist making this relief would have been working from a small drawing or painting. Like the one found in the database of the RKD. Forcing the artist to imagine the lower portion of the body. Resulting in a relief that looks more like a primitive drawing than like a real person.

Father and son Hartsinck

When we propose the man with the sword is Carel Hartsink, the man in the portrait, we may also propose the other Dutch official represented among the donors of this religious building would be his son, Willem Carel Hartsinck. Willem Carel was the governor of the VOC in India in 1679-80, the highest authority at the time, giving him the power and the money to participate in this Hindu ceremonial construction project. Which actually was a highly illegal and risky activity for any VOC official at any time! As far as I can tell, this participation of a VOC official in a Hindu religious project is a unique occurence. Having himself immortalized, together with his dead father, on this Hindu mandapam which was constructed for ceremonies on the occasion of the total eclipse of the 30th of march 1680.

An extraordinary monument for two extraordinary people, eclipse March 30 1680

Altogether an extraordinary monument of the two centuries of Dutch presence and trade in India. As well as a monument to two extra-ordinary men, father and son Hartsinck, Carel en Willem Carel. Undoubtedly also a monument of the love and respect of a son for his dead father.

But there is more to this story even than the obvious. Because Willem Carel had a very unusual, even a unique, background. And his career was far from ordinary. Because Willem Carel was half Japanese. Which makes his career at the VOC not an average one, but highly unusual, especially in the 17th century. The life-stories of Carel and his half Japanese sons Willem Carel and Pieter Hartsinck are extraordinary.

More about father and sons Hartsinck and their extraordinary careers in my next blog. To be continued…

Harihara Subramanian

I have been curious about this mandap off ECR and collected a few photos as reference. Thank you for throwing light on many of my questions. I had not thought of the eclipse connection until now.

Ramjee

Lovely note. Interesting research. TFS.

Paul van der Velde

Hi Liebeth,

Wat een fantastische en geloofwaardige ontdekking!!

Harts,

Paul

Christek

An unknown story found and lively told, part of the dutch-indian history.